Unsettling Flesh / Dissecting the Gaze. On the Simultaneity of the Contemporary

The present happens without us being able to stop

it - all that remains and that is constant are images.

We are confronted with the ever-changing images,

moving or statistical, human or android, digital or

analog, which affect us visually and whose power of

effect hardly anyone can escape, since they structure our

everyday modes of perception. At the beginning of the

development of this Western present was the emergence

of transport infrastructures that detached time from

its cosmological order and organized it capitalistically

by linking it to space (the movement from a start to

a destination). Instead of the planets determining

time, the desire for productivity and profit now guided

time and placed it under their service. To recount this

seems anachronous and simplistic in light of what

seems today to be the degenerate state of this history:

everything simultaneously and always everywhere.

Time and space dissolve completely. Our conditions of

existence are constantly in radically differently weighted

relationships, the worlds of feeling ambiguous. Living

in the simultaneity of temporal and spatial axes, in

an image overload, our attention economies are in a

state of permanent overload. In their works, artists

Minda Andrén and Dominika Bednarsky confront this

constantly complicating world by critically situating our

material reality.

Where can places of retreat from this overturning

present lie? Nature no longer forms a place of retreat.

In this consequence, the body appears as the ultimate

mystery that can never be fully understood, contrary

to all attempts at taxonomization. We are not only

permanently surrounded by images, reflections,

disciplining of the body, but also - and precisely because

of this - permanently thrown back on our own body.

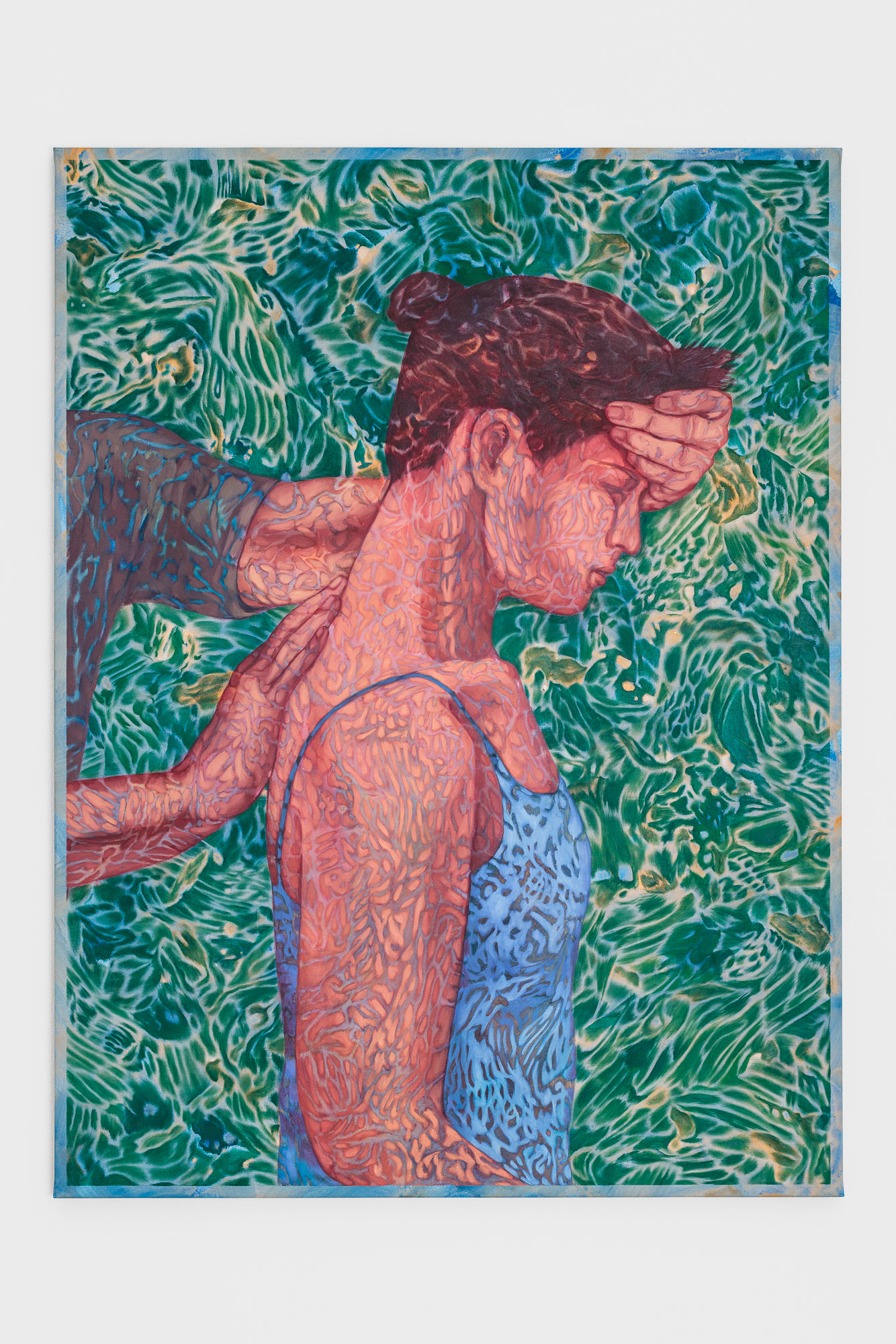

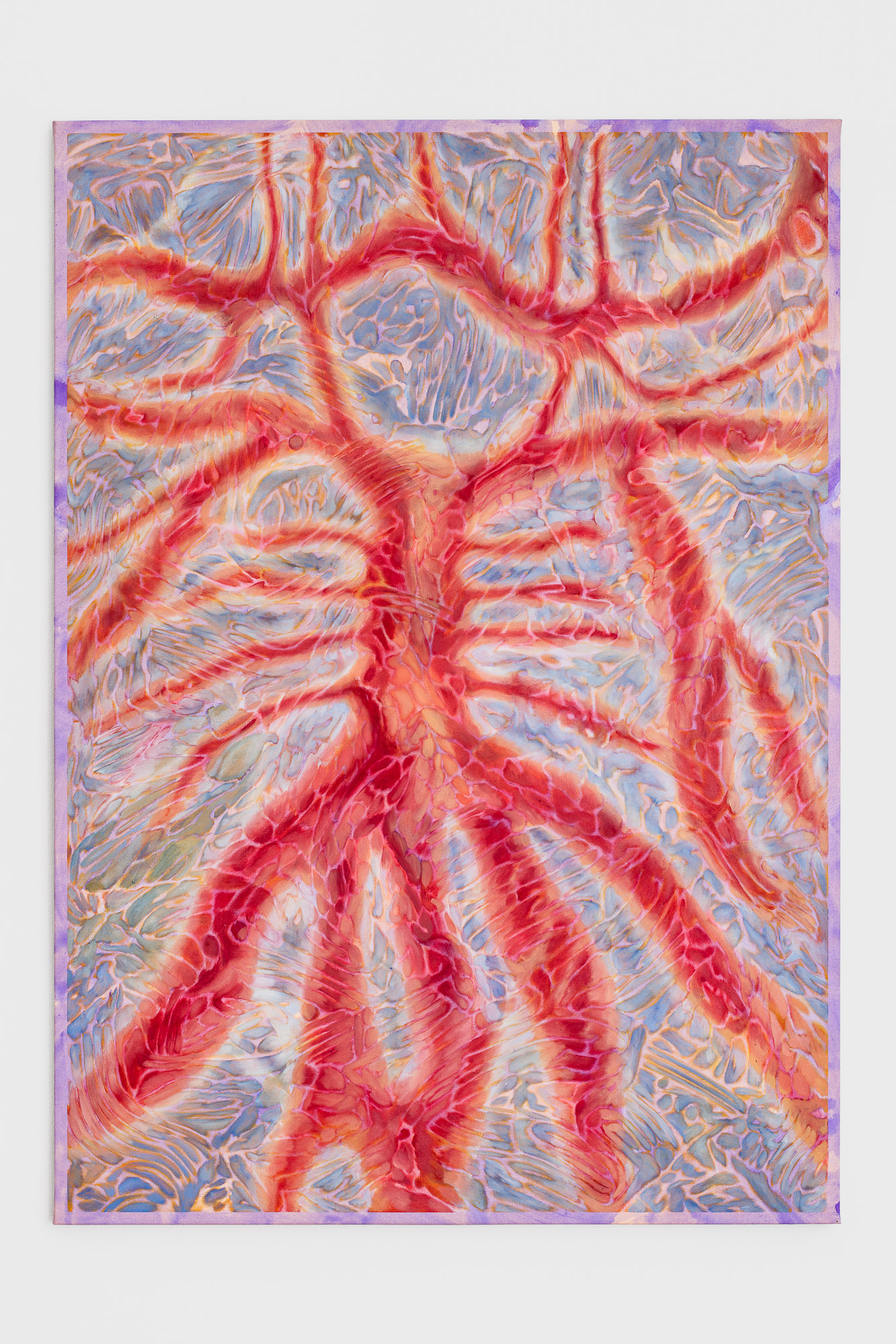

Minda Andrén’s paintings offer a projection or reflection

surface for this paradoxical overload. Layer by layer, she

encounters images of corporeality in her painting - that

of the artist encountering the canvas, and at the same

time with the cultural-historical facets of the topos

body. At the edges of the canvases, the surface of the

first layer flashes through; a rough painterly gesture

arranges the first color surface of the canvas. Starting

from this structure, Andrén develops her body paintings.

She draws the motifs from a wide variety of sources. The

branching structure on the canvas, an abstract system

of fibers, or almost a cortex?, become the materiality

of painting made flesh and dissects the motifs lying on

it. By singularizing the motifs and integrating them,

they return to the body of painting. The simultaneous

existence of the layers and their formal-aesthetic

incorporation of arbitrary images dissect the viewer’s

gaze, but also allow a dissecting gaze through the

disclosure of the layers.

The motifs of Dominika Bednarsky ceramics borrow

from everyday culture. They achieve their absurdity

through the central subject that is part of each sculpture:

minced meat. The yellow horse has a mane made of

minced meat, the hen is covered with eggs made of

minced meat, the cake is not a cream cake but a minced

meat cake. The ceramics obviously cite the German

phenomenon of Mettfiguren. Forming large figures out

of meat is only conditionally a sign of humor, but rather

of excessive consumption, if not medieval gluttony. Not

entirely unironically, however, Bednarsky combines cute

motifs (little mice, bows, little birds) with the easily

perishable food. Being cute or cuteness, as an aesthetic

feeling and object description of the contemporary,

always stand in an ambiguous relationship. That which

is cute attracts and appears to be positive in the first

instance; however, something is cute only because it

appears powerless or impotent to the judging subject.

Cuteness is likewise a leading commodity aesthetic;

as an aesthetic feeling, it is closely associated with

convenient consumption. Bednarsky’s ceramics open

up the space for the named ambiguous feelings to

take place simultaneously, overlapping and denying an

absolute aesthetic judgment. 1 The glossy and ultra-

precise surfaces draw the eye, the incorporation of

the sculpted mincemeat repels. They hurl the viewing

subject into a constantly actualizing situation with no

clear end. In this way, Bednarsky plays with the viewer’s

voyeuristic desire by defamiliarizing familiar motifs that

belong to collective social memory and are overlooked

in shop windows. It only becomes clear how ambiguous

contemporary aesthetic feelings can be.

Rather than a way out, or a redemptive response, both

positions offer a mirror to the visual complexity of the

present. Their materialities and fleshy surfaces have a

disquieting effect; they reorganize modes of perception

by appropriating them and shattering them again. In this

way, Andrén and Bednarsky’s works create a visual in-

between space that stands apart from the present, yet can

only take place with and within it. Artistic practice does

not seem to be a way out, but certainly a brake on the

present taking place in and with constant simultaneity

- despite unclear aesthetic feelings, it situates us in the

here and now, encloses time and space in its dimensions

for a moment, and ultimately throws us back on ourselves

again and again.

Photo Credits: Simon Veres